NEW YORK (AP) — In the winter of 1789, around the time George Washington was elected the country's first president, a Boston-based printer quietly launched another American institution.

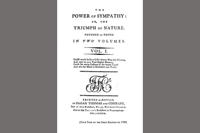

William Hill Brown's “The Power of Sympathy,” published anonymously by Isaiah Thomas & Company, is widely cited as something momentous: the first American novel.

Around 100 pages long, Brown's narrative tells of two young New Englanders whose love affair abruptly and tragically ends when they learn a shocking secret that makes their relationship unbearable. The dedication page, addressed to the “Young Ladies of United Columbia” (the United States), promised an exposé of “the Fatal consequences of Seduction” and a prescription for the "Economy of Human Life."

Outside of Boston society, though, few would have known or cared whether “The Power of Sympathy” marked any kind of literary milestone.

“If you picked 10 random citizens, I doubt it would have mattered to any of them,” says David Lawrimore, an associate professor of English at the University of Idaho who has written often about early U.S. literature. “Most people weren't thinking about the first American novel.”

What the first American novel was like

Subtitled “The Triumph of Nature. Founded in Truth,” Brown's book is in many ways characteristic of the era, whether its epistolary format, its Anglicized prose, its unidentified author, or its pious message. But “The Power of Sympathy” also includes themes that reflected the aspirations and anxieties of a young country and still resonate now.

Dana McClain, an assistant professor of English at Holy Family University, notes that Brown was an outspoken Federalist, believing in a strong national government, and shared his contemporaries' preoccupation with forging a stable republican citizenry. The letters in “The Power of Sympathy” include reflections on class, temperament and the differences between North and South, notably the “aristocratic temper” of Southern slave holders that endangered “domestic quietude," as if anticipating the next century's Civil War.

Like many other early American writers, fiction and nonfiction, Brown tied the behavior of women to the fate of the larger society. The novel's correspondents fret about the destabilizing “power of pleasure” and how female envy “inundates the land with a flood of scandal.” Virtue is likened to a “mighty river” that "fertilizes the country through which it passes and increases in magnitude and force until it empty itself into the ocean.”

Brown also examines at length the ways novels might be a path to corruption or a vehicle to uplift, mirroring current debates over the banning and restrictions of books in schools and libraries.

“Most of the novels with which our female libraries are overrun are built upon on a foundation not always placed on strict morality, and in the pursuit of of objects not always probable or praiseworthy,” one of Brown's characters warns. “Novels, not regulated on the chaste principles of true friendship, rational love, and connubial duty, appear to me totally unfit to form the minds of women, of friends, or of wives.”

Brown was likely more interested in shaping minds than in literary glory. “The Great American Novel” is a favorite catchphrase but wasn't coined until the 1860s. During Brown's lifetime, novels were a relatively crude art form and were valued mostly for satire, light entertainment or moral instruction. Few writers identified themselves as “novelists”: Brown was known as a poet, and essayist and the composer of an opera.

Even he recognized the book’s lower stature, writing in the novel's preface: “This species of writing hath not been received with universal approbation."

How it became considered the first

“The Power of Sympathy” was commonly cited as the first American novel in the 1800s, but few bothered debating it until the 20th century. Scholars then agreed that honors should belong to the first written and published in the United States by an author born and still residing in the country.

Those guidelines disqualified such earlier works as Charlotte Ramsay Lennox's “The Life of Harriot Stuart” and Thomas Atwood Digges' “Adventures of Alonso.” Another contender was "Father Bombo's Pilgrimage to Mecca,” a prose adventure by college students Hugh Henry Brackenridge and Philip Freneau, both of whom went on to prominent public careers. Written around 1770, the manuscript was later believed lost and wasn't published in full until 1975.

Brown's novel was unexamined for so long that only in the late 19th century did the public even discover he had written it. Many had credited the Boston poet Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton, whose family had endured a scandal similar to the one in “The Power of Sympathy.”

In 1894-95, editor Arthur W. Brayley of the Bostonian serialized the novel in his magazine, identifying Morton as the author. But after being contacted by Brown's niece, Rebecca Vollentine Thompson, Brayley published a lengthy correction, titled “The Real Author of the ‘Power of Sympathy.’”

Thompson herself added a preface to a 1900 reissue, noting that Brown was close to Morton's family and alleging that the publication had been “suppressed” because Brown had bared an “unfortunate scandal.”

A clock maker's son, Brown was a Boston native, likely born in 1765. He was well-read, connected, culturally conservative and politically minded; one of his first published writings was an unflattering poem about Daniel Shays, the namesake for the 1786-87 rebellion of impoverished Revolutionary War veterans in Massachusetts. Brown is also the author of several posthumous releases, including the play “The Treason of Arnold” and the novel “Ira and Isabella.”

His unofficial standing as “America's First Novelist” did not lead to broader fame. The novel, currently in print through a 1996 edition from Penguin Classics, remains more of interest to specialists and antiquarians than to general readers.

Brown was not yet 30 when he died in North Carolina, in 1793, from what is believed to be malaria. He apparently never married or had children. No memorials or other historical sites are dedicated to him. No literary societies have been formed in his name.

His burial site is unknown.