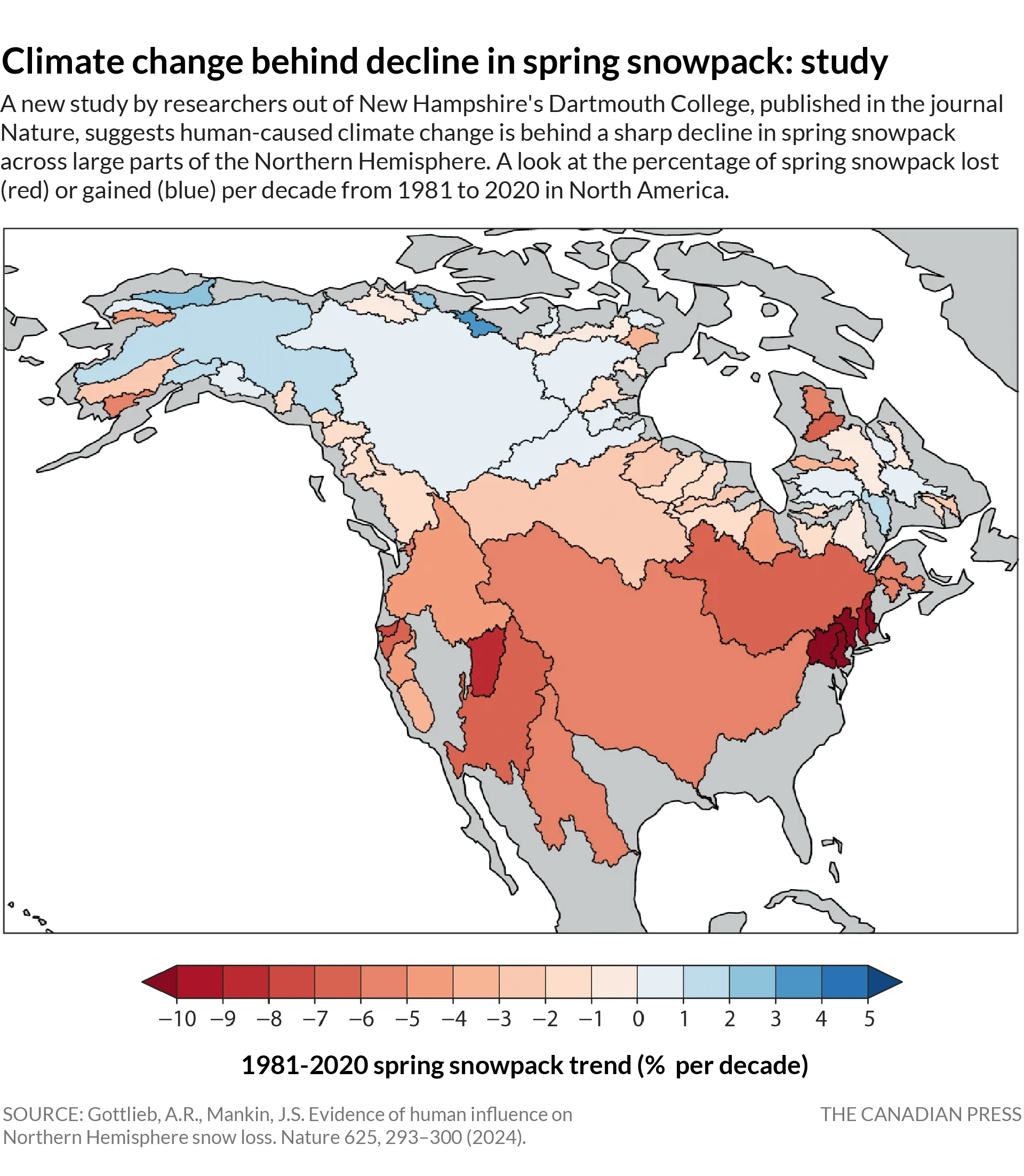

TORONTO - Human-caused climate change is behind a decline in spring snowpack across parts of Southern Canada and the Northern Hemisphere, says a new study that offers widespread caution of how a warming planet could transform winter and affect water security.

The study out of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, cuts through the noise of standalone measurements and models to find climate change has altered spring snowpack across 31 major river basins in the Northern Hemisphere, including a decline in the large St. Lawrence-Great Lakes basin.

"We find that, in the language of the (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), it is virtually certain... that human emissions have contributed to the observed pattern of March snowpack trends," the study said.

John Pomeroy, a leading Canadian expert in water resources and climate change who was not part of the study, said parts of Canada are already seeing the effects of lower spring snowpack in the form of droughts and wildfires.

"It shows Canadians that what we've relied upon in our history as a country, which is reliable snowpack that provides water in the spring, is becoming less reliable, especially in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence where most Canadians live, but also showing signs that it's happening in the West," said Pomeroy, a University of Saskatchewan professor and Canada Research Chair in water resources and climate change.

Snowpack plays a number of crucial roles, Pomeroy said. It insulates soil in the winter and replenishes lakes and wetlands in the spring. Local economies built around the ski industry depend on it. As it melts, it helps reduce the risk of wildfires, powers hydroelectricity dams and irrigates farmland.

"That affects society in so many ways," Pomeroy said.

The authors of the new study say although observations in the St. Lawrence basin had previously suggested snowpack trends were small and insignificant, their results show human-caused climate change was responsible for a seven per cent drop in March snowpack per decade over 40 years.

PhD candidate Alex Gottlieb said he and his co-author, associate professor Justin Mankin, arrived at the results after comparing several major data sets to confidently pinpoint March snowpack trends from 1981 to 2020. The authors then compared what they found to climate models simulating snowpack levels in the absence of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Gottlieb said despite some inconsistencies between individual data sets, when you put them together, it's clear the long-term snowpack trend for some major basins is "really only consistent with a world in which we've emitted as we have."

Although people in snowy locales will often anecdotally refer to recent snowpack declines as a sign of a warming planet, Gottlieb said he was surprised by the lack of confident claims in the scientific literature. The study points to the latest IPCC report, which concluded with high confidence that springtime snowpack in the Northern Hemisphere has "generally declined" since 1981, but was still unclear where, when and by how much human-caused climate change had actually altered the snowpack.

That's partially because snowpack -- the mass of accumulated snow -- can vary greatly across distances and time, and there are lots of ways to measure it.

But by bringing all those observations together and comparing them with some of the most advanced climate models, the study considerably strengthens the recent IPCC claim about the links between climate change and snowpack melt, the authors said.

"There's exceedingly little chance that you can see something that we've observed in the real world absent of human interference in the climate system," said Gottlieb, a PhD candidate in Dartmouth's ecology, evolution, environment and society program.

The study also came up with what the authors consider a snow loss tipping point. In regions where average winter temperatures remain below -8 C, snowpack stays relatively consistent. In colder regions, including Northern Canada and Siberia, it can increase, since a warming atmosphere holds more moisture that continues to fall as snow.

But on the other side of that -8 C threshold, with more chances of days at or near freezing, regions start to see accelerating snow loss. It's what Gottlieb called a "snow-loss cliff."

"You start to see these really big and actually accelerating losses of snowpack, where each additional degree of warming is taking away a bigger and bigger chunk of your snowpack, on average," said Gottlieb.

Most of the Northern Hemisphere's snow mass is in consistent, colder regions, but the remaining 20 per cent is in areas hovering near that snow-loss cliff, the study said.

Crucially, however, those are also the places with the most human demand. Eighty per cent of the hemisphere's population lives in those snow-dependent areas near or at that cliff, the study said.

Spring snowpack loss has been particularly sharp in northeastern and southwestern U.S., along with parts of Europe, where the study found declines of between 10 and 20 per cent per decade over the past 40 years.

While the study shows some snowpack declines in large parts of Western Canada and increases in the North, the authors said they could not clearly identify the role of climate change. But Pomeroy said that's part of the limits of a large-scale study, not the absence of climate impacts in those areas.

"It's being very, very careful to show that on a global scale, there are some trends there," he said of the Dartmouth study.

"Other studies, local studies, have shown those relationships."

He noted the Dartmouth study focused on data from March, earlier than when the snowpack peaks across much of Western Canada. Snowpack measurements are also often taken at mid-elevation, he said, when the biggest declines in those areas happen at lower elevation.

Pomeroy said the study should be a sign to Canadian decision makers to bolster snow measurement efforts and start planning to manage water resources more carefully.

This report by üСÜꪤüýò¿Øéóæòêü was first published Jan. 10, 2024.